No Ragrets (But Maybe Some Regrets)

Yom Kippur 5786, Delivered at Temple Shalom of Newton

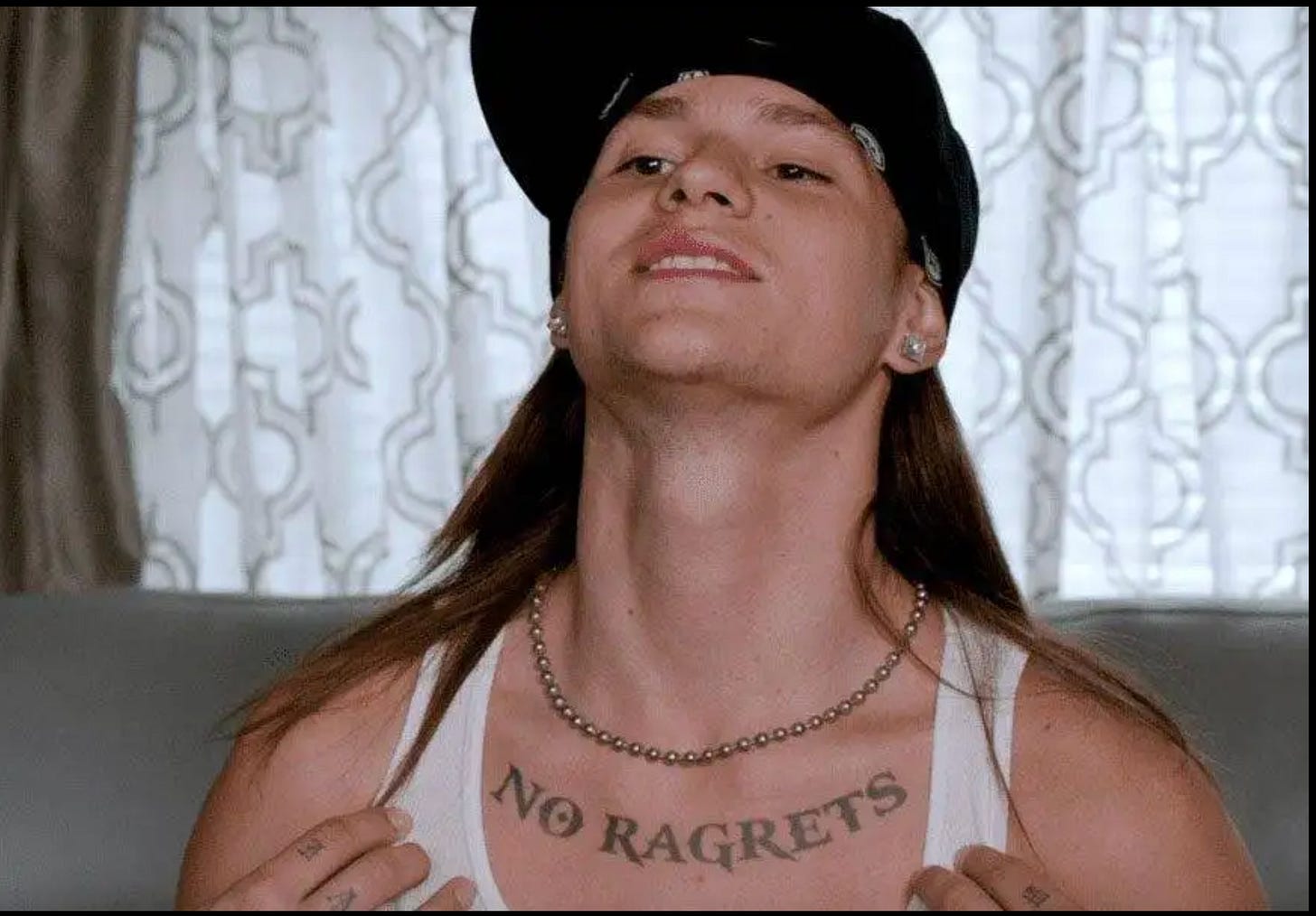

“Hey, those are cool tattoos, man!” David remarks.

He’s sitting across from Scottie, who is wearing a tank top that reveals several tattoos, including one that runs along his collarbone inked in blocky letters.

“What is that one right there?” David, played by actor Jason Sudeikis, asks, pointing at Scottie’s tattoo.

“Oh, this?” Scottie responds. “That’s my credo. No regrets.”

“How about that,” David remarks. “You have no regrets?” He asks.

“Nope,” says Scottie.

David follows up. “Like… not even a single letter?”

“No, I can’t think of one,” Scottie replies.

I bet you can see where this is going, in this quite forgettable comedy, “We’re the Millers.”

You see - Scottie had no regrets. But regretfully, he didn’t use spell check when getting his tattoo. Thus, emblazoned on his collarbone was a powerful credo:

No Ragrets.

R-A-G-R-E-T-S.

It may not surprise you then to know that there is a $100 million-a-year industry focused on tattoo removal because almost 1 in every 5 people who has a tattoo… eventually ra-gret it.1

But not all regrets are easily laughed off or lasered away. Some regrets cut much deeper.

**

One morning, Alfred woke up to quite a shock. It was 1888 and that morning in the local newspaper, he saw an obituary that read: “Le marchand de la mort est mort” - the merchant of death is dead. The obituary described a man who had made a fortune from the invention of dynamite… noting that it was a weapon that killed people faster than the world had ever before seen.

It was so shocking to Alfred because Alfred had invented dynamite, but for the purpose of construction and mining. It was also shocking to Alfred because he loathed war AND while he wasn’t in the best of health,2 he wasn’t dead. His brother Ludwig had recently died and the newspaper had made a big mistake.

Alfred deeply regretted what he read about himself, especially regretting that his legacy would be one of destruction and death.

Regrets. Lots of them.

***

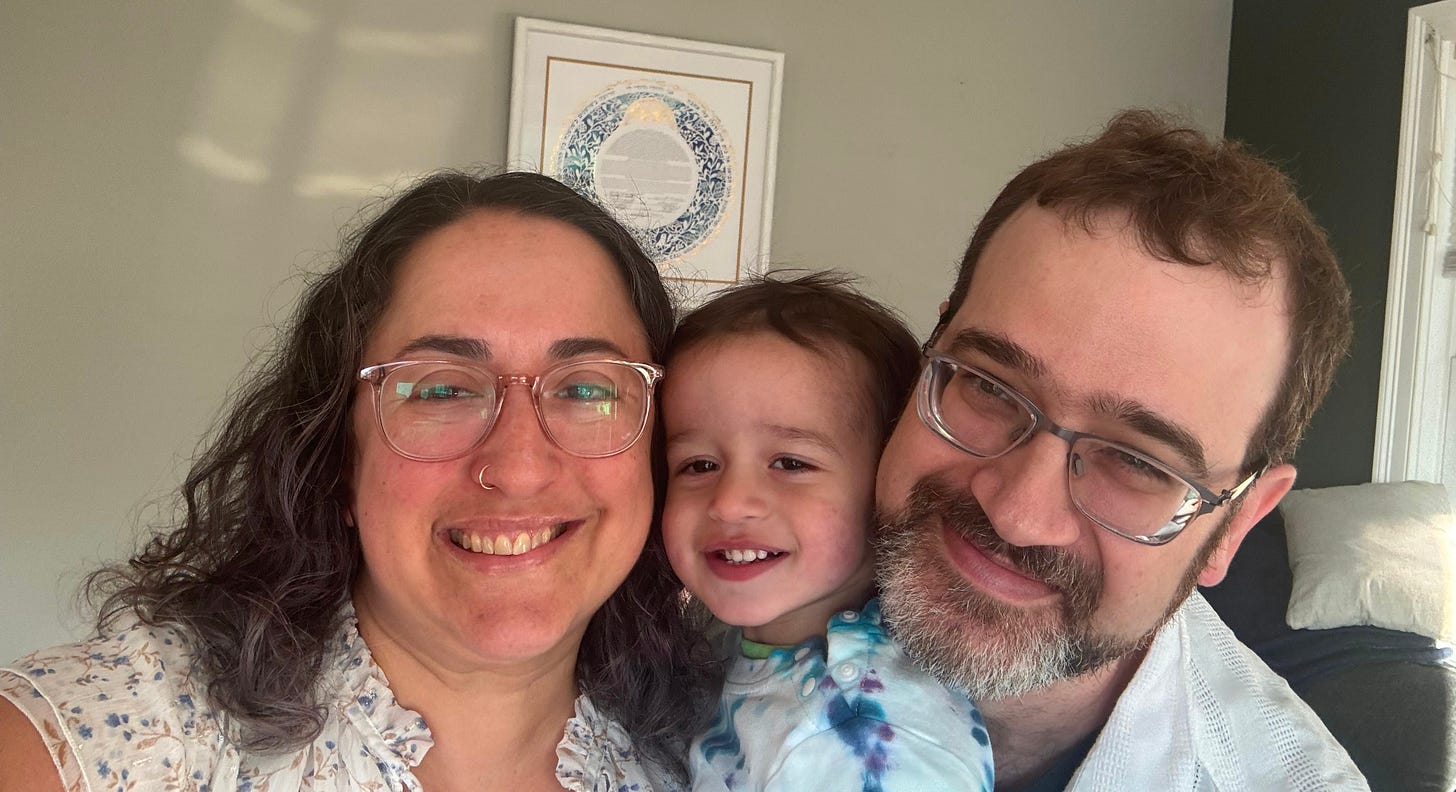

She sat down at her computer, day after day, for hours. Bleary eyed, annoyed, self-critical. Skimming books, articles, music lyrics. Stopping mid conversation or task to write down ideas as they popped into her mind.

Why can’t I figure out how to start? She wondered as her thoughts spiraled. What if what I want to say and what they expect me to say don’t align? What if what they need to hear and I need to write are out of sync? What if I make someone mad? What if I don’t inspire them?

And why is the new season of “Love is Blind” premiering during Kol Nidre? Tell me that’s not anti-Semitic.

Rabbi Jen Gubitz smiled to herself. At least they can’t say I didn’t talk about anti-Semitism in my sermon.

She knew that no matter what she said (or didn’t say), she might wind up with regrets. Should I talk about Israel, about democracy, or about brokenness? Should I speak about joy or hope?

Should I admit my regrets of leadership? If only I had said more about my deep love of Israel. If only I had stood up sooner for ceasefire and concern for innocent Gazans? Should I admit that I wish I had the courage, the energy, to step deeper into healing the soul of our world but I just want to spend time with my longed for child? (And also what are we going to have for dinner?)

Jen worried, as she often does, that she would regret getting it all wrong. But she also knew that the regret itself —the caring enough to worry—meant her heart was still in it.

**

Whether inked in our body, on our hearts, or on our souls, what are we supposed to do with the ever human emotion of regret? Our culture sends mixed messages. We skydive out of planes yelling YOLO - you only live once. We buy pillows at TJ Maxx embroidered with “Live Your Best Life” or “Everything happens for a reason.”

We shrug our shoulders, and remark: “It is what it is.”

We pretend we know Latin: Carpe Diem! Or French: C’est La Vie! Or lyrics from Rent: Forget regret or life is yours to miss.

So which is it? Should we remove regret? Reframe it? Hide from it? Embrace it? Run from it?

Author Daniel Pink spent years researching regret and came to a surprising conclusion. In his book: The Power of Regret: How Looking Backward Moves Us Forward, Pink explained: “The purpose of this book is to reclaim regret as an indispensable emotion —and to show you how to use its many strengths to make better decisions, perform better at work and school, and bring greater meaning to your life.”3

He distilled his research into two simple yet urgent conclusions:4

1. Regret makes us human.

2. Regret makes us better.

Pink discovered that most regrets fall into four core categories: Foundation regrets, boldness regrets, connection regrets, and moral regrets.

Foundational regrets are the “If only I had…” sort of regret, resulting from “failures of foresight and conscientiousness. They often start with a choice. At some early moment, we face a series of decisions” about foundational aspects of our lives. Sometimes they are regrets for which we are personally responsible; and sometimes they are due to circumstances beyond our control.5

“If only I had saved money instead of spending it all.”

“If only I had taken school more seriously.”

“If only I had taken care of my health when I was younger.”

We look back from our present perch wistful, melancholy, mournful even.

Boldness regrets are the “What ifs?” of our lives. The risks not taken. The dreams left unpursued.

“What if I had started that business?”

“What if I had traveled when I had the chance?”

“What if I had asked them out?”

These regrets whisper to us about the paths not taken, the courage we didn’t summon, the moments when we played it safe. We look back from our present perch wistful, melancholy, mournful even.

Connection regrets emerge out of relationships that have come undone or remain incomplete

“If only I’d reached out.”

“If only I hadn’t let that friendship fade.”

“If only I had reconciled with them before it was too late.”

And finally, Pink describes the smallest category of regrets - moral regrets. Moral regrets represent only 10% of Pink’s data, but moral regrets are often the ones that hurt the most. Like:

“I wish I hadn’t cheated.”

“I wish I hadn’t lied to cover myself.”

“I wish I had done the right thing when it mattered.”

These are the regrets that keep us up at night, and make us wonder about the kind of person we really are. We look back from our present perch wistful, melancholy, mournful even.

Despite only being 10% of Pink’s data, I suspect that the past few years, the moral regret many of us have felt as we witness the ethical and moral breakdown of our society, weighs most heavily upon us.

What are the regrets you hold?

Is it a foundation you failed to build?

Is it boldness you never summoned?

Is it a connection you let slip away?

Is it a moral failing that haunts you?

And more importantly - and apt for the work of Yom Kippur:

What will you regret in the future if you don’t change course now?

These questions are heavy, grievous even, which is actually fitting. The word “regret” comes from the Old French regreter, meaning to lament, to weep or mourn. Like the loss of a loved one, some regrets may feel like a weight we’ll carry forever.

But we are not alone in our regret. Not only because we sit among one another today reflecting on our rights and wrongs, with regret and remorse. But our tradition teaches that God also felt regret.

In Genesis, at the very end of the very beginning, we encounter God looking back on creation and humankind: “God saw how great was human wickedness on earth—how every plan devised by the human mind was nothing but evil all the time. Vayinachem Adonai, And God regretted having made humankind on earth.

With a sorrowful heart, וַיִּתְעַצֵּ֖ב אֶל־לִבּֽוֹ/Va’yit’atzev el libo, God said, “I will blot out from the earth humankind whom I created—humans together with beasts, creeping things, and birds of the sky; for I regret that I made them.”(Genesis 6:5-7)

Let that sink in.

God— the Creator of the universe— looks at creation and feels regret and deep sorrow. God - Creator of the universe - who on this holy day we call Avinu Malkeinu, Our Father, Our King - God is heartbroken.

God’s next move is shocking, wiping out the world and starting from scratch with some guy named Noah and his ark. A holy temper tantrum, a holy do-over. Holy regret.

The ancient rabbis struggled with this idea that God, Avinu Malkeinu, Parent and Sovereign, could make a mistake. And their uncertainty hinged on one word - which our Hebrew speakers may have picked up on.

Vayinachem Adonai

The Torah translates it as God regretted, but vayinachem shares the same root as nichum - comfort - like nichum aveilim, comforting mourners.

And there’s another meaning still. Later in Exodus after the sin of the golden calf, God is ready once again to wipe out humanity, BUT:

Vayinachem Adonai

This time the Torah says that God reconsidered, repented, and changed course on that calamitous decision.

Regret? Comfort? Change? Which one is it?

The ancient rabbis can’t figure it out.6

Regret? Comfort? Change? The answer is YES.

God regrets.

God grieves.

God begins again.

God rebuilds.

God reconnects.

God changes.

God finds comfort.

Chicago based Rabbi Wendi Geffen offers: “To regret is to grieve what was, to feel the ache of what cannot be undone, but it is also to be comforted because regret tells us that we care, that our hearts are still tender. And regret in our tradition is also the seed of change. The possibility that tomorrow can be lived differently than yesterday.”

Paraphrased by Rabbi Jon Spira-Savett, the great Rav Kook taught “that simply reciting the things we regret opens up an immediate channel to the Divine. That practice is viddui, oft translated as confession, but much richer… Kook suggests that the regrets we deeply feel help us understand what we actually value most. Regrets show us the ideal self we already believe in, the person we want to live up to being. Regret is one of the most important reminders of who and what we care about. It’s one thing to articulate a life philosophy - regret shows us concretely what philosophy we already are striving to live by.”7

That sounds like Yom Kippur in a nutshell, right? (sorry, I regret mentioning food.)

Yom Kippur is rooted in regret - which in Old English - from gret - can also mean to re- greet. Yom Kippur is the moment of greeting again our grief and our growth, staring the highs and lows of our humanity in the face.

Author David Whyte teaches “to regret fully is to appreciate how high the stakes are in an average human life. Fully experienced, regret turns our eyes, attentive and alert to a future, possibly lived better than your past.”8

Yom Kippur’s act of teshuvah - turning and returning to our best selves - is a holy process refined by Maimonides, but blueprinted for us by God.

Regret.

Re - Greet.

Grieve.

Begin.

Rebuild.

Reconnect.

Change.

Comfort.

When author Daniel Pink said that regret makes us human, he wasn’t entirely correct. Regret does make us human, but regret also reflects back to us what is within each of us-- and that is the spark of the Divine.

**

Even though it was from a terrible movie, I knew I’d “ragret” leaving out that first story. The third story was obviously about me. But in the second story, I left out an important detail. I didn’t tell you the last name of Alfred, the inventor of dynamite. You see, Alfred’s last name was Nobel. And eight years after the unusual and grievous opportunity to read his own obituary, Alfred Nobel signed his final will and testament and left his tremendous wealth “to fund a series of prizes for those who, during the preceding year, shall have conferred the greatest benefit on mankind.”9

Alfred Nobel got to rewrite his ending. Yom Kippur is our opportunity to do the same.

And it starts now.

Regret makes us human.

Regret makes us better.

Be nice to everyone in the parking lot today AND

Embrace regret.

Reach out to that person you’ve avoided.

Reinvest your time and attention in the ones you love.

Take a bold step, try something new.

Stand up, speak out.

Grieve. Apologize.

Forgive. Find comfort.

And maybe, don’t get a tattoo.

May we all be inscribed and sealed in the Book of Lives Well Lived.

Shana Tovah.

Daniel Pink, The Power of Regret, p. 10-11.

https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/history/how-dynamite-spawned-nobel-prizes

Daniel Pink, The Power of Regret, p. 13.

Pink, p. 14.

Pink, p. 86.

The initial sources for this sermon were inspired by sermons by R’ Aaron Alexander and R’ Wendy Geffen.

As paraphrased and explained by Rabbi Jon Spira-Savett likely on Kook’s Orot Hateshuvah 16:2 https://sinaiandsynapses.org/content/through-regret/

David Whyte, CONSOLATIONS: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words, 2015.

https://www.history.com/articles/did-a-premature-obituary-inspire-the-nobel-prize

I regret it took me two weeks to get around to reading this! It's wonderful! Thank you, Rabbi Jen!

It was wonderful to listen to this in Temple, and just as wonderful to read it here. Thank you, Rabbi Jen, for your endless store of wit, wisdom, and compassion.